mercoledì 30 agosto 2017

sabato 26 agosto 2017

giovedì 24 agosto 2017

mercoledì 23 agosto 2017

martedì 22 agosto 2017

domenica 20 agosto 2017

giovedì 17 agosto 2017

mercoledì 16 agosto 2017

martedì 15 agosto 2017

venerdì 11 agosto 2017

giovedì 10 agosto 2017

mercoledì 9 agosto 2017

FAANG Vs. The 4 Horsemen Of The '90s

By Gary GordonStock Markets31 minutes ago (Aug 09, 2017 03:26PM ET)

During the late 1990s tech boom, investors fell in love with the remarkable price appreciation of four mega-cap public corporations: Microsoft (NASDAQ:MSFT), Intel(NASDAQ:INTC), Cisco (NASDAQ:CSCO) and Dell(NYSE:DVMT). They became known as the ‘four horsemen’ for their unparalleled influence. In fact, at points in 1999 and 2000, the group accounted for as much as 55%-60% of the NASDAQ’s price movement.

During the late 1990s tech boom, investors fell in love with the remarkable price appreciation of four mega-cap public corporations: Microsoft (NASDAQ:MSFT), Intel(NASDAQ:INTC), Cisco (NASDAQ:CSCO) and Dell(NYSE:DVMT). They became known as the ‘four horsemen’ for their unparalleled influence. In fact, at points in 1999 and 2000, the group accounted for as much as 55%-60% of the NASDAQ’s price movement.

Perhaps ironically, some of these hold-forever stocks began losing a bit of their appeal as dot-com mania kicked into gear. Investors began believing that the 21st century had ushered in an entirely different paradigm on how and what to invest in. Regardless of traditional metrics like profits or sales or book value, ‘New Economy’ standouts like Sun Microsystems, JDS Uniphase and EMC (NYSE:EMC) were capturing investor imagination as well as market share.

As a national talk radio personality in the late 1990s and early 2000, I cautioned listeners about the sustainability of the gains that they had come to expect. Naysayers insisted I was too bearish. Of course, most of those naysayers had never witnessed what a bear market could do. Indeed, near the very top in March of 2000, a prominent writer at the Motley Fool castigated my guidance to have a plan for getting off the surfboard when the wave ceased to be worthy of the risky ride.

Never raise cash… that was what the financial community advised the public. It did not matter that investors had been staring at the most extreme overvaluation in stock market history. It did not matter that the Oracle (NYSE:ORCL) Of Omaha, Warren Buffett, had been laughed into obscurity for his obstinate opposition to the pricing for revolutionary technologies. And it sure as heck did not matter that a young buck on terrestrial radio, yours truly, chose not to give an “all systems go” approval.

In reality, I had been defensive, downshifting form 70% stock to 50% stock. The fundamental overvaluation required me to be less aggressive. Yet I did not make a tactical shift to a genuinely bearish 33% highest quality stock allocation until key technicals broke down.

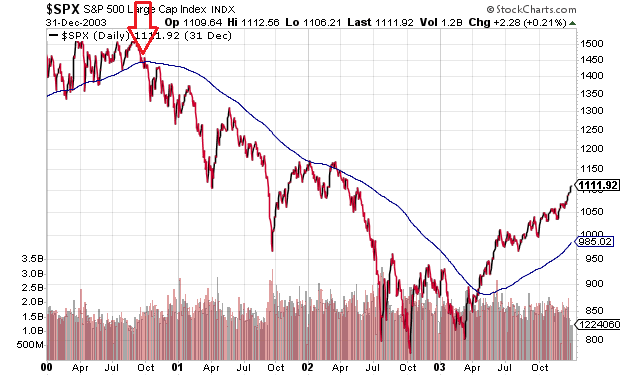

For example, when the S&P 500’s month-end closing price had finished below its 200-day moving average on September 30 (2000), the technical evidence was clearly indicating a marketplace shift toward risk aversion. I lowered my stock allocation and raised my cash allocation. Moreover, I let tens of thousands of folks know about what I was doing, helping many of them to sidestep the bulk of the tech bubble’s implosion.

Although I may have been learning to tie my own snow boots in Kindergarten during the early 1970s, I am keenly aware of the crazy love investors gave to the ‘Nifty Fifty’ stocks. As always, mainstream financial advice told investors to hold all of those stalwarts throughout their lifetimes. Even if those companies were selling at outrageous multiples of 40x, why would you sell them? General Electric (NYSE:GE), Xerox (NYSE:XRX), Sears(NASDAQ:SHLD), Polaroid, Coca-Cola (NYSE:KO) – no reason to ever sell those legends of industry.

Unfortunately, there were a few flaws with the idea of holding the ‘Nifty Fifty’ to infinity and beyond. First, even when a business appears viable for decades into the future, like a Coca-Cola or a GE, an individual stock itself is not guaranteed to remain “nifty.” Innovative new companies supplant the supposed untouchables. Second, similar to the four horsemen’s predominance in the NASDAQ’s price movement, the Nifty Fifty had been responsible for most of the price gains of the S&P 500 and most of the losses in the S&P 500’s decade-long struggles to recover capital.

It’s not that nominal dollar amounts would not still be accumulated via dividends in this period had an investor held on for 10 years. Yet why must one ignore the risk of losing so much in the first place, as though the 1973-1974 bear couldn’t have been deeper? The Nasdaq managed to lose 80% of its value this century. The Dow managed to lose 90% the previous century. Isn’t Japan still down some 50% after 28 years? Why should investors wait 17-plus years to recover purchasing power via inflation-adjusted returns, when less volatile assets show potential to outperform head-to-head and on a risk-adjusted basis?

I have put this forward before, but it is worth repeating: the 10-month simple moving average has beaten buy-n-hold over the last 90 years. Do the homework on the Ivy Portfolio yourself. Examine taxable and tax-deferred accounts. The risk-adjusted performance (e.g., Sharpe, standard deviation, etc.) is undeniable. The head-to-head may be a close call. Nevertheless, if you never wish to find your nest egg falling from $1,400,000 to $700,000, and then deciding whether to stay the proverbial course because you’ve been assured that the U.S. stock market has always recovered before, perhaps Job #1 should be to protect capital from severe downtrends.

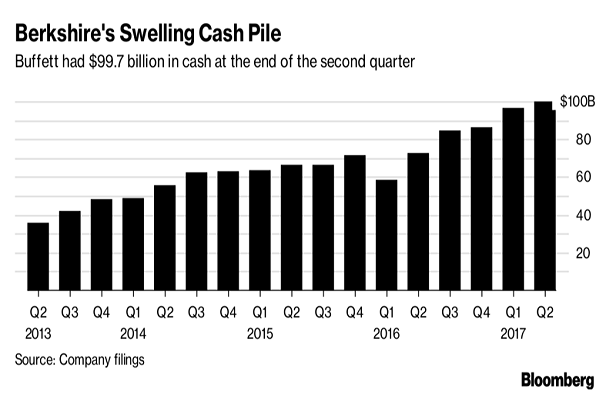

Consider Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway (NYSE:BRKa) (BRK.B). In 4 years, his cash war chest has bloated from $40 billion to $100 billion. In spite of the pile, Buffett’s team clearly does not see an opportunity to buy awesome corporations at a fair price. Additionally, he is keenly aware that the higher the price he pays, the lower the prospective future returns. Is it any surprise that the Oracle of Omaha finds the pickings rather slim?

Not only is Buffett willing to wait for attractive deals (since few exist), yet he is known for waiting patiently for sharp corrections and bears. Who would be better positioned to take advantage if stocks and/or the economy struggle mightily?

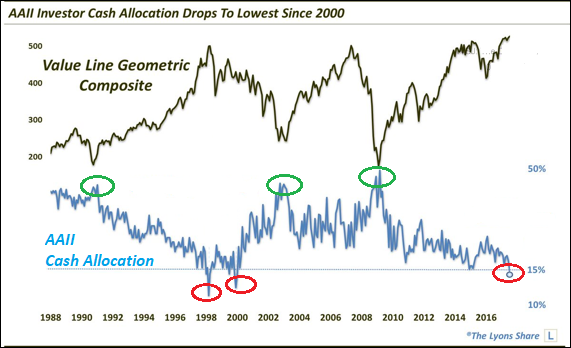

Signs of overextended bullishness may already be emerging. The American Association of Individual Investors (AAII) has not seen cash allocations as low as they are today since the Asia Currency Crisis in 1998 and the tech bubble of 2000.

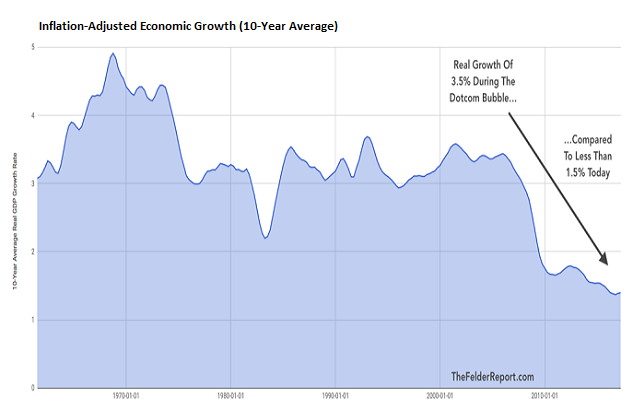

For those who may sheepishly accept the notion that the economy is humming along, they may want to get a gander at the leverage that households, government(s) and corporations have employed to achieve meager results. Consider real GDP using a 10-year average. Does anyone get the sense that our economic enhancements since the Great Recession is commensurate with taking federal government obligations from $10.5 trillion to nearly $20 trillion? Is that bang for the buck? And can we really accelerate from here?

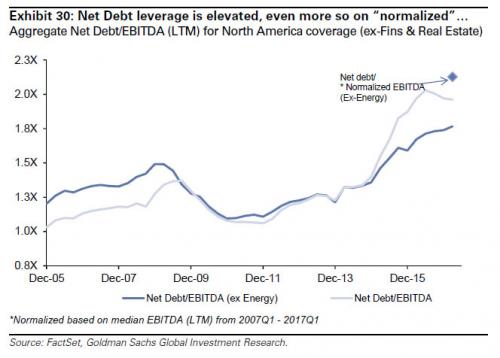

I might have a little more confidence had corporations used the doubling of their debt levels for productive purposes. Sadly, due to interest obligations (now and in the future), coupled with the most leverage in corporate history, something may have to give. Earnings per share could suffer. Dividend growth could slow. And, in some instances, present promises abandoned.

This is not to say that the stock market will cease to grind higher. Nor would I suggest that a 5% to 10% correction would fail to become the next dip buying opportunity.

What I will say, however, is that the ‘FAANG” phenomenon smells like rookie spirit. Facebook (NASDAQ:FB), Amazon (NASDAQ:AMZN), Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL), Netflix(NASDAQ:NFLX) and Alphabet (NASDAQ:GOOGL) are hardly unbeatable. They’re actually vulnerable.

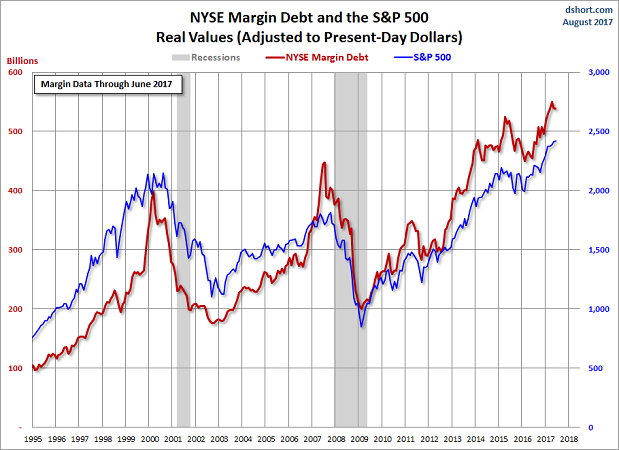

Not only did the overwhelming bulk of the Nifty Fifty reach their limits of growth, not only did three of the four horsemen hit theirs as well, but ‘FAANG’ exists at a time where leverage in the financial system has never been greater. It follows that when margin calls eventually occur, which leveraged stocks are likely to get slammed the hardest?

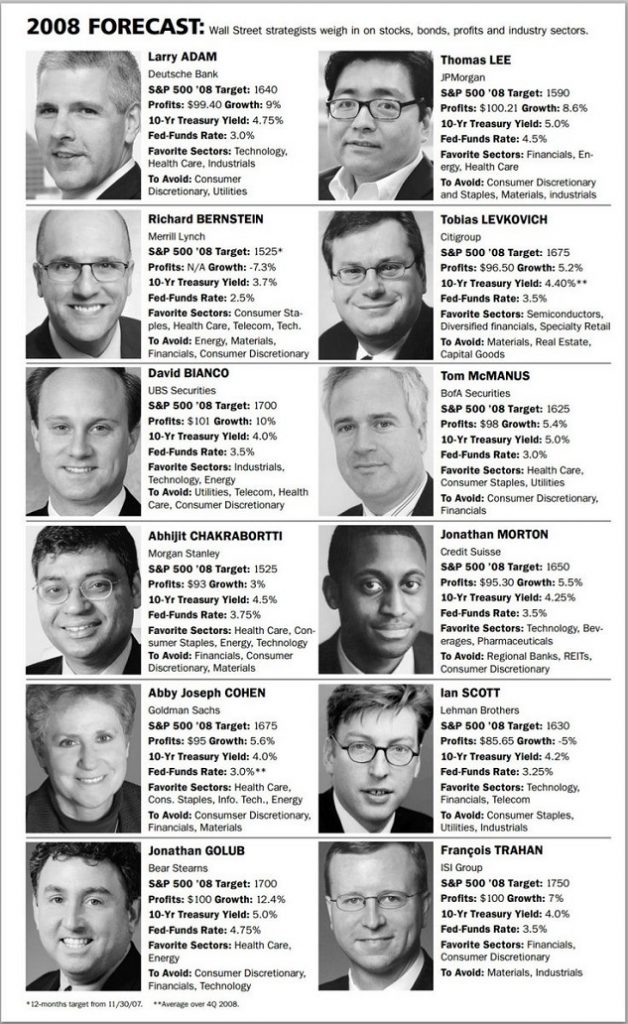

Let me close with a bit of media hype from the year of the financial crisis, 2008. There are those who will tell you that they could see the recession and the stock market sell-off coming. Some did. Investor’s Business Daily interviewed me at the very start of January in 2008, where I gave the odds of a recession at 80%. That didn’t mean I sold everything… I did not. I warned people to employ an exit strategy for reducing some exposure to the riskiest assets in their portfolios.

On the flip side, the biggest names at the biggest institutions on Wall Street had no intention (or no ability) to caution the investing public. On the contrary. Every single one of them believed that 2008 would be a banner year from earnings as well as stock prices in the S&P 500. They collectively projected stocks would finish the year in a range from 1525-1750, though it ended at 903!

In other words, do not expect Wall Street to help you with a plan to protect capital. Their job is to get you to “Buy, buy, buy!”

martedì 8 agosto 2017

venerdì 4 agosto 2017

giovedì 3 agosto 2017

mercoledì 2 agosto 2017

It Won't Be Long Now - David Stockman Warns Amazon Is The New Tech Crash

It won’t be long now. During the last 31 months the stock market mania has rapidly narrowed to just a handful of shooting stars.

At the forefront has been Amazon.com, Inc., which saw its stock price double from $285 per share in January 2015 to $575 by October of that year. It then doubled again to about $1,000 in the 21 months since.

By contrast, much of the stock market has remained in flat-earth land. For instance, those sections of the stock market that are tethered to the floundering real world economy have posted flat-lining earnings, or even sharp declines, as in the case of oil and gas.

Needless to say, the drastic market narrowing of the last 30 months has been accompanied by soaring price/earnings (PE) multiples among the handful of big winners. In the case of the so-called FAANGs + M (Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix, Google and Microsoft), the group’s weighted average PE multiple has increased by some 50%.

The degree to which the casino’s speculative mania has been concentrated in the FAANGs + M can also be seen by contrasting them with the other 494 stocks in the S&P 500. The market cap of the index as a whole rose from $17.7 trillion in January 2015 to some $21.2 trillion at present, meaning that the FAANGs + M account for about 40% of the entire gain.

Stated differently, the market cap of the other 494 stocks rose from $16.0 trillion to $18.1 trillion during that 30-month period. That is, 13% versus the 82% gain of the six super-momentum stocks.

Moreover, if this concentrated $1.4 trillion gain in a handful of stocks sounds familiar that’s because this rodeo has been held before. The Four Horseman of Tech (Microsoft, Dell, Cisco and Intel) at the turn of the century saw their market cap soar from $850 billion to $1.65 trillion or by 94% during the manic months before the dotcom peak.

At the March 2000 peak, Microsoft’s PE multiple was 60X, Intel’s was 50X and Cisco’s hit 200X. Those nosebleed valuations were really not much different than Facebook today at 40X, Amazon at 190X and Netflix at 217X.

The truth is, even great companies do not escape drastic over-valuation during the blow-off stage of bubble peaks. Accordingly, two years later the Four Horseman as a group had shed $1.25 trillion or 75% of their valuation.

More importantly, this spectacular collapse was not due to a meltdown of their sales and profits. Like the FAANGs +M today, the Four Horseman were quasi-mature, big cap companies that never really stopped growing.

Now I’m targeting the very highest-flyer of the present bubble cycle, Amazon.

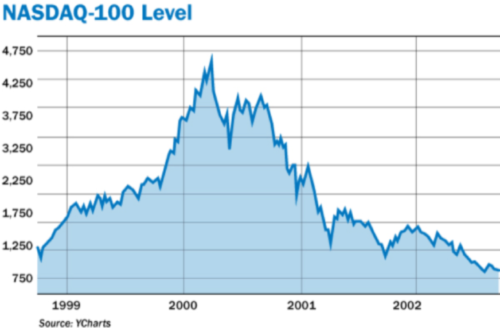

Just as the NASDAQ 100 doubled between October 1998 and October 1999, and then doubled again by March 2000, AMZN is in the midst of a similar speculative blow-off.

Not to be forgotten, however, is that one year after the March 2000 peak the NASDAQ 100 was down by 70%, and it ultimately bottomed 82% lower in September 2002. I expect no less of a spectacular collapse in the case of this cycle’s equivalent shooting star.

In fact, even as its stock price has tripled during the last 30 months, AMZN has experienced two sharp drawdowns of 28% and 12%, respectively. Both times it plunged to its 200-day moving average in a matter of a few weeks.

A similar drawdown to its 200-day moving average today would result in a double-digit sell-off. But when — not if — the broad market plunges into a long overdue correction the ultimate drop will exceed that by many orders of magnitude.

Amazon’s stock has now erupted to $1,000per share, meaning that its market cap is lodged in the financial thermosphere (highest earth atmosphere layer). Its implied PE multiple of 190X can only be described as blatantly absurd.

After all, Amazon is 24 years-old, not a start-up. It hasn’t invented anything explosively new like the iPhone or personal computer. Instead, 91% of its sales involve sourcing, moving, storing and delivering goods. That’s a sector of the economy that has grown by just 2.2% annually in nominal dollars for the last decade, and for which there is no macroeconomic basis for an acceleration.

Yes, AMZN is taking share by leaps and bounds. But that’s inherently a one-time gain that can’t be capitalized in perpetuity at 190X. And it’s a source of “growth” that is generating its own pushback as the stronger elements of the brick and mortar world belatedly pile on the e-commerce bandwagon.

Wal-Mart’s e-commerce sales, for example, have exploded after its purchase of Jet.com last year — with sales rising by 63% in the most recent quarter.

Moreover, Wal-Mart has finally figured out the free shipments game and has upped its e-commerce offering from 10 million to 50 million items just in the past year.

Wal-Mart is also tapping for e-commerce fulfillment duty in its vast logistics system — including its 147 distribution centers, a fleet of 6,200 trucks and a global sourcing system which is second to none.

In this context, even AMZN’s year-over-year sales growth of 22.6% in Q1 2017 doesn’t remotely validate the company’s bubblicious valuation — especially not when AMZN’s already razor thin profit margins are weakening, not expanding.

Based on these basic realities, Jeff Bezos will never make up with volume what he is losing in margin on each and every shipment.

The Amazon business model is fatally flawed. It’s only a matter of the precise catalyst that will trigger the realization in the casino that this is another case of the proverbial naked emperor.

Needless to say, I do not think AMZN is a freakish outlier. It’s actually the lens through which the entire stock market should be viewed because the whole enchilada is now in the grips of a pure mania.

Stated differently, the stock market is no longer a discounting mechanism nor even a weighing machine. It’s become a pure gambling hall.

So Bezos’ e-commerce business strategy is that of a madman — one made mad by the fantastically false price signals emanating from a casino that has become utterly unhinged owing to 30 years of Bubble Finance policies at the Fed and its fellow central banks around the planet.

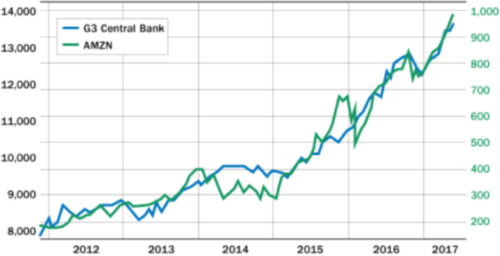

Indeed, the chart below leaves nothing to the imagination. Since 2012, Amazon stock price has bounded upward in nearly exact lock-step with the massive balance sheet expansion of the world’s three major central banks.

At the end of the day, the egregiously overvalued Amazon is the prime bubble stock of the current cycle. What the Fed has actually unleashed is not the healthy process of creative destruction that Amazon’s fanboys imagine.

Instead, it embodies a rogue business model and reckless sales growth machine that is just one more example of destructive financial engineering, and still another proof that monetary central planning fuels economic decay, not prosperity.

Amazon’s stock is also the ultimate case of an utterly unsustainable bubble. When the selling starts and the vast horde of momentum traders who have inflated it relentlessly in recent months make a bee line for the exits, the March 2000 dotcom crash will seem like a walk in the park.

martedì 1 agosto 2017

Why Bitcoin Is Not 'Digital' Gold Or Silver

By Keith WeinerMarket Overview6 hours ago (Aug 01, 2017 12:16AM ET)

Precious Metals Supply and Demand Report

That’s it. It’s the final straw. One of the alternative investing newsletters had a headline that screamed, “Bitcoin Is About to Soar, But You Must Act by August 1 to Get In”. It was missing only the call to action “call 1-800-BIT-COIN now! That number again is 800 B.I.T..C.O.I.N.”

Bitcoin, daily. In terms of the gains recorded between the lows of 2009 and the recent highs (from less eight hundredths of a US cent per bitcoin, or $1 = 1,309.2 BTC, the first officially recorded value of BTC, to $3,000 per bitcoin, or $1 = 0.000333333 BTC), the bubble in bitcoin by now exceeds every historical precedent by several orders of magnitude, including the infamous Tulipomania and Kuwait’s Souk-al-Manakh bubble.

In percentage terms BTC has increased by about 392,760,000% in dollar terms (more than 392 million percent) since its launch eight years ago. Comparable price increases have otherwise only occurred in hyperinflation scenarios in which the underlying currency was repudiated as a viable medium of exchange. Our view regarding its prior non-monetary use value and hence its potential to become money differs slightly from that presented by Keith below. We will post more details on this soon, for now we only want to point out that we believe there is room for further debate on this point. [note from Pater Tenebrarum] .

Is it about to go up? Maybe. We don’t know. And everyone should by now be skeptical of all “rocket to take off on XYZ date” claims. Between them, surely these newsletters have predicted thousands of the past zero blastoffs of gold and silver since 2011.

We have discussed bitcoin in the past, to argue that it is not money (a video here, and articles here and here). Bitcoin is not money because it is not a good. It’s just a number in a database. Money is a kind of good (genus). The most marketable kind (differentia).

Money must be a good because we are physical beings in a physical world and final payment — which is not demanded all the time, or even often — must be a physical thing that you can hold and touch in your physical hands. Bitcoin is not a physical good, so it represents, not final payment, but intermediate payment. It is not final until you trade the bitcoin for a real good. In the language of economics, a real good has utility apart from one’s hope to exchange it for something else. Bitcoin has no utility apart from this hope of its value in exchange, its price.

There is not one price but always two prices: bid and offer. When one has a thing and relies on someone else to buy it (or accept it in exchange), it is the bid price which is relevant. The offer price may be close above the bid, or it may be much higher. Typically sellers are reluctant to sell below their cost, but that has nothing to do with buyers. Buyers make a bid based on how they value it (or not).

This fact right here is sufficient to debunk the labor theory of value. Suppose producing a painting takes you 50 hours of labor plus $100 in materials. That does not matter. If your name is Banksy, people might be happy to pay tens of thousands of dollars for the painting. If your name is Keith Weiner, not so much (Keith is not known for having any skill at painting, though he can take some mean photographs).

For all commodities, for all real goods, for all tangible products, there is always a bid. Even a junk car is worth something to the scrap dealer. Even sand is worth something to the landscape contractor.

If a commodity is useful for something, it will have a robust bid. The price may be low or high, but the bid will be set by those who have a productive purpose in mind. If you can buy something, add a little bit of value from labor (e.g. cleaning it up) and sell it for $1,000 then you are willing to pay up to, say, $900.

Take copper. Copper can be used for wiring and plumbing (and many other things). If you manufacture plumbing, and you know that with a dollar worth of labor you can turn copper into a pipe that sells for $3.75, what are you willing to pay for the copper? Perhaps you would go up to $2.50 (it’s now about $2.85). If the price of copper drops, this new buyer will come into the market (for now, plumbing is made of plastic).

In this light, we now get to the 64 billion dollar question. What is the bid on bitcoin? What is it useful for, and who would buy it for that purpose?

Right now, bitcoin is a lot of fun. Its price is being driven up by frenzied speculators. With each new price level, proponents become bolder and more aggressive. Bitcoin will replace the dollar, bitcoin will go up to $1,000,000, the dollar is failing, get yours before August 1, etc. Many of these arguments were popular when the price of gold was rising relentlessly up through 2011.

But what is the ultimate bid? Where is the floor, where it cannot go below, because it is just too profitable to buy it, transform it into a higher-value good to sell at a profit? Where is the floor where individuals will buy more and more because they want bitcoin in their living room, or in the tank of the car, or in their refrigerator, or in their basement? It doesn’t exist, does it?

This is not a prediction for tomorrow morning. Indeed timing these things is impossible. However, there will come a point when the speculators turn. Perhaps their collective thumbs will move the planchette on the price-chart Ouija board to paint an ugly chart pattern (much uglier than head-and-shoulders). Whatever its initial cause, what will happen is clear in light of the above discussion.

The price of bitcoin could drop to any level. Incidentally, bitcoin could be used in exchange as it is now, whether its price is $0.01 or $1,000,000.

People often say that bitcoin is like gold, or even say it is “digital gold”. They are just trying to cash in on gold’s good name. The problem of the bid is another key difference between bitcoin and gold. Gold is an extremely useful commodity. Bitcoin is not any kind of commodity at all. It does not have a real bid at all, only the ever-changing bid of the fickle speculator.

Fundamental Developments

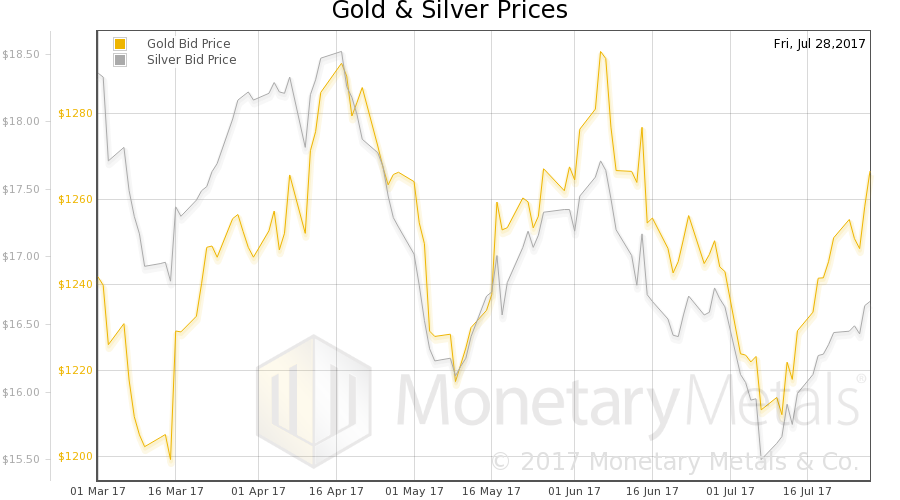

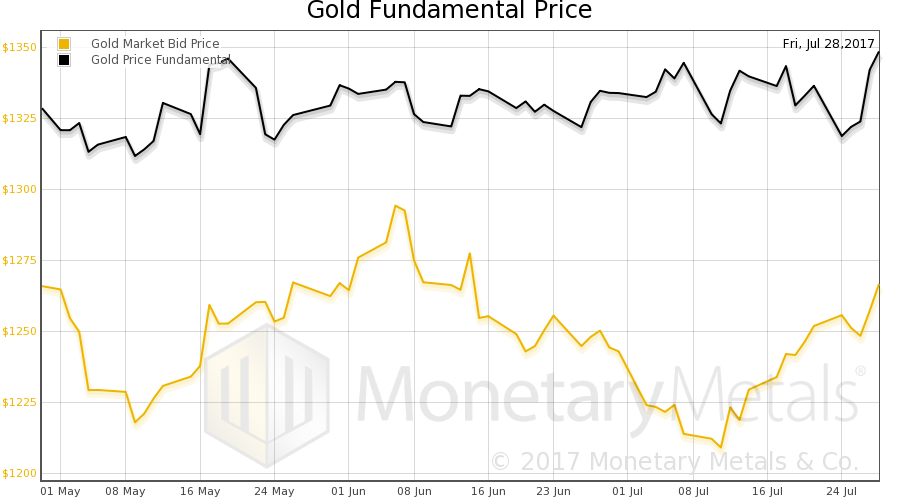

The prices of the metals rose some more last week, with gold +$13 and silver +$0.24. However, that leads to the question: is it speculators getting ahead of the fundamentals, or is it real?

Three weeks ago, with the price of gold $56 lower and the price of silver $1.15 lower than today, we asked if that was capitulation. We cited some circumstantial evidence (plus rising scarcity of both metals as measured by the co-basis). We did not call for a moonshot, but a “normal trading bounce within the range.”

Today it is time to ask if the bounce is down, and if now is the time for a normal correction. And if it the answer is the same for both metals. We will show graphs of the true measure of the fundamentals. But first charts of their prices and the gold-silver ratio.

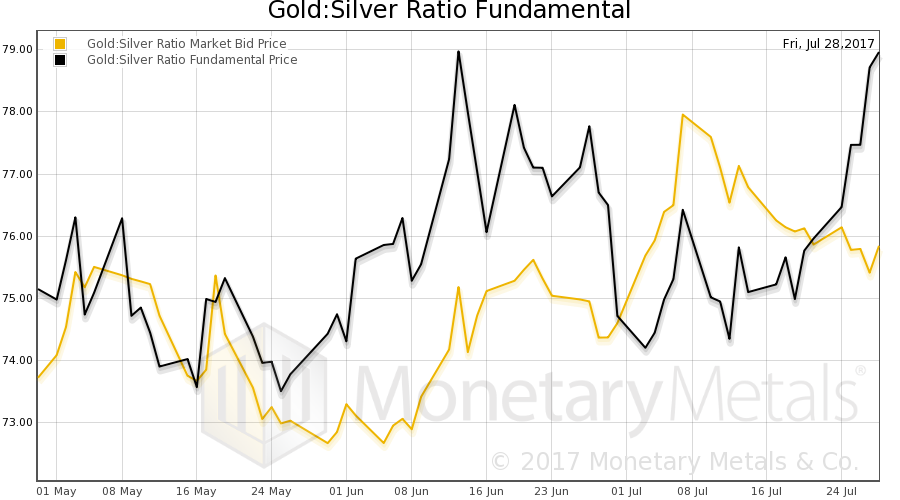

Next, this is a graph of the gold price measured in silver, otherwise known as the gold-to-silver ratio. The ratio moved down slightly this week. We find it interesting that the ratio did not fall farther.

In this graph, we show both bid and offer prices for the gold-silver ratio. If you were to sell gold on the bid and buy silver at the ask, that is the lower bid price. Conversely, if you sold silver on the bid and bought gold at the offer, that is the higher offer price.

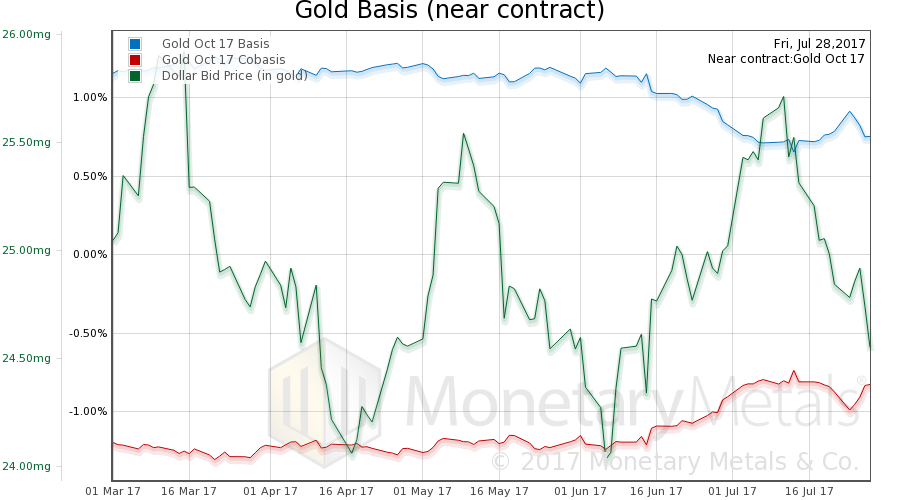

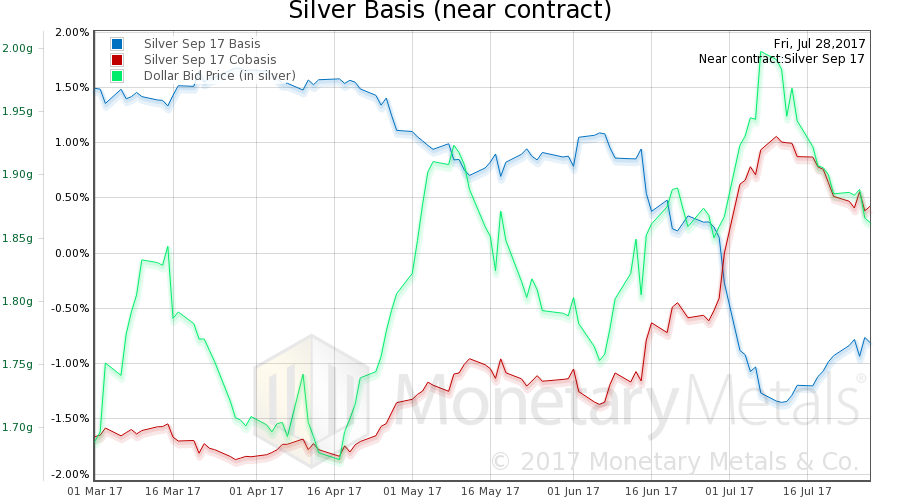

For each metal, we will look at a graph of the basis and co-basis overlaid with the price of the dollar in terms of the respective metal. It will make it easier to provide brief commentary. The dollar will be represented in green, the basis in blue and co-basis in red.

Here is the gold graph.

October gold basis and co-basis and the dollar priced in milligrams of gold

The dollar fell again this week (the mirror image of the rising price of gold). As the dollar fell, the co-basis increased — gold became more scarce.

Rising price + rising scarcity = rising fundamental price.

Now let’s look at silver.

In silver, unlike in gold, as the dollar has dropped (i.e., the price of silver measured in dollars has risen), the metal has become more abundant.

Our calculated silver fundamental price fell about 50 cents this week, or about 75 cents in the past few weeks. So while the price of gold may continue to rise to perhaps over $1,300, the price of silver could be a bit weaker. We calculate a fundamental gold-silver ratio of about 79.

Fundamental gold-silver ratio vs. market ratio based on bid prices

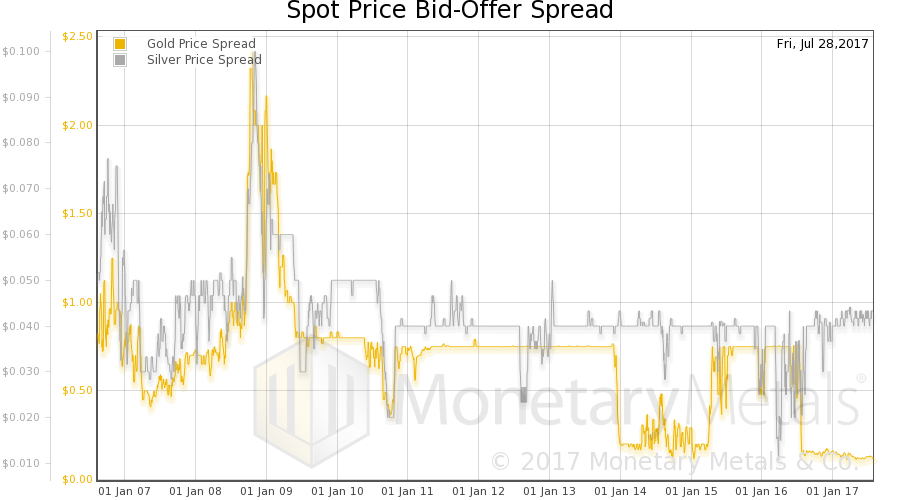

Coming back to the bid-ask spread, we thought we would publish another chart off our website. This one shows the bid-ask spread of spot gold and spot silver.

Bid/ask spreads of gold and silver

There are two salient features. First, note that the spread is really tight in both metals (though while the spread in gold dropped in mid-2016, in silver it increased). It is currently around 12 cents in gold. An ounce of gold is over $1,200 and the difference between bid and ask is $0.12 or 0.01 percent! In silver, it is around 4.2 cents, or 0.25 percent. Gold is more liquid, much more liquid.

Second, when the financial system buckled and nearly collapsed in 2008, the spreads widened to $2.40 and $0.10 in gold and silver, or 0.33 percent and 1.05% respectively. Compared to real estate in a normal market, both metals are extremely tight. Compared to illiquid assets during the peak of the crisis, it’s incredible.

We recall a story of a guy who bought a famous painting by an Old Master near the top in 2007. He paid, as we now recall, around $13 million. During the crisis, he was forced to sell it. He got $100,000. We assume the offer price on such a painting would still be $10 million or more. But $100,000 was the bid.

Iscriviti a:

Commenti (Atom)